Translating the language of belay to the concept of community.

BY BELLA BUTLER

PHOTOS BY JAKE BURCHMORE

Rain pelts the windshield of Conrad Anker’s white Chevy Silverado as he speeds toward the entrance of the Gallatin Canyon south of Bozeman, Montana. The wipers are working overtime, but the view of the castle- like cliffs jutting out from steep treed mountainsides is as runny as the watercolor paintings on his desk at home, where we’ve just left. Manoah Ainuu, Anker’s climbing partner for the day, sits shotgun.

The truck continues southbound toward the destination, a relatively secret climbing area Anker and his friends have been developing for going on six seasons, but Anker’s becoming anxious.

“In baseball, they do call the game on account of rain,” he says. Even for someone like Anker, who insists he “has to climb three days a week,” fervor must yield to weather.

Ainuu doesn’t show any signs of apprehension; instead selecting Mac Miller songs to play through the truck’s stereo. In contrast, Anker ponders alternative ways to spend the day. He wishes he’d brought his drill. If he can’t climb, he muses, this time could’ve been spent setting new routes on his latest project, dubbed “The Retirement Wall.” Calling this retirement might seem like a joke, and it kind of is. Developing new crags, climbing more days than not, co-authoring books, advocating for climate and social justice, obliging constant interview requests, fulfilling the duties of a sponsored athlete, and maintaining his role as a committed father and husband is a far cry from retirement, but relative to decades as one of the most accomplished professional climbers and alpinists, this third act of life is performed at a slower tempo for 60-year-old Anker.

Anker’s accepted the fact that he won’t be climbing today, but a few minutes after entering the canyon, the dark clouds brighten with diffused sunlight, and the rain ceases. The weather yields back. Out the window, local revered climbs come in and out of view, among them some developed by Anker. Much of his career is remembered for feats like the first ascent of the Shark’s Fin on India’s nearly 22,000-foot Meru; the first ascent of the Continental Drift route on El Capitan; the first ascent of the east face of Vinson Massif in Antarctica; and the first ascent of Badlands on the southeast face of Torre Egger in Patagonia.

He’s summited Everest three times, each expedition significant in its own right: the first summit he discovered the body of climber George Mallory; the second he free climbed the second step—the highest free climb in the world; and the third he completed without supplemental oxygen. And yet, this southwest Montana canyon, with its limestone buttresses and glittering granite gneiss towers, is as much a defining backdrop of his life as the Himalaya or Yosemite or the Arctic. This place is his home; it’s where he started visiting in the mid-90s to climb with his late climbing partner and best friend, Alex Lowe, who was killed in an avalanche in 1999 on an expedition he and Anker were on together. It’s where he’s lived since 2001, raising three sons with his wife, Jennifer Lowe-Anker. As evidenced in the metal anchors adorning the rocks in surrounding canyons, he’s left a mark on this place. And it, too, has left a mark on him.

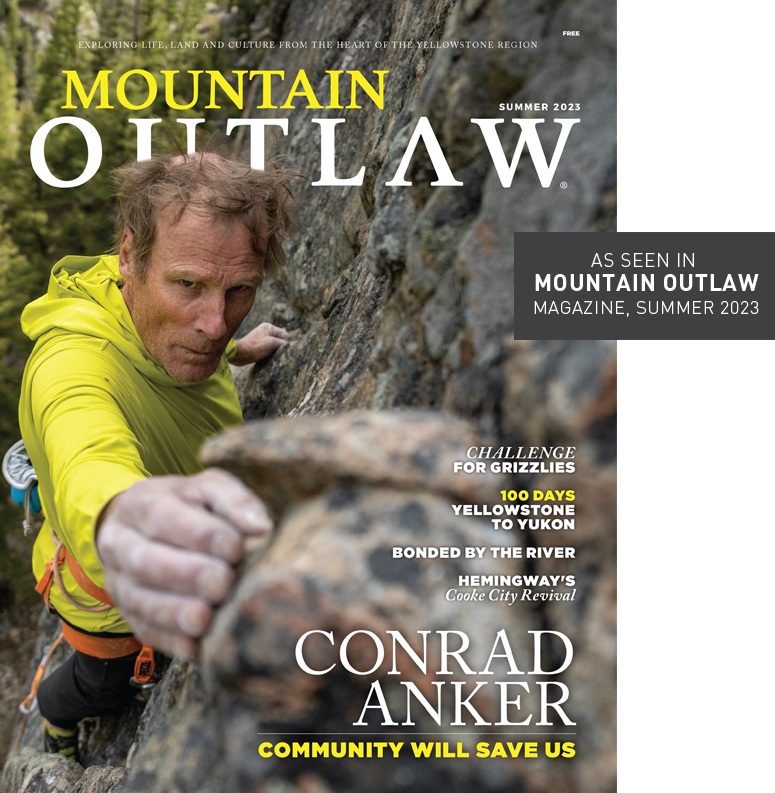

The Silverado comes to a halt at a wide and unsuspecting turnout. The climbing’s been deemed back on, and Anker eagerly drops the tailgate and loads himself up with gear. The 55-liter pack is a feather weight compared to what he’s hauled on big expeditions, but it still looks like a hefty load against his wiry frame. Anker shows signs of his age: a thinning mess of blonde hair on his head; horizontal wrinkles on his forehead, perhaps from a lifetime of looking up. But his appearance gives him away as an athlete. He’s strong in the lean way that climbers are, and his eyes reflect the paradox of the alpinist: intense joy weighted by loss.

“The beauty of when we get out climbing is that it’s changing the paradigm of how humans communicate with other humans.” – Conrad Anker

Like any of us, Anker’s world view is largely informed by his religion. But he doesn’t believe in any sort of God or afterlife; he believes in gravity. And just as gravity is an objective force, he talks about things in a matter-of-fact sort of way: our mortality is inescapable; our desires are intrinsic; our fate is dirt. But when it comes to human society, he doesn’t accept all that is. He talks exuberantly about politics, denouncing what he sees as a seeping culture of hate and inequity. He laments climate inaction. But he offers prescriptions of hope, one being community. Simply put, he says, community is caring for others. It’s shared passion. It’s held wisdom. It’s common language. For him, community is climbing. And he thinks climbing can save us. Or at the least, climbing can teach us about community. And maybe that can save us.

“The beauty of when we get out climbing is that it’s changing the paradigm of how humans communicate with other humans,” he says. “[In] all experiential outdoor activity, the rewards are intrinsic: a view, or feeling good about doing a climb. You don’t have anything. I mean, you can collect rocks and things, but it’s usually the intrinsic and you seek that reward. And in the process of doing that, the manner in which you communicate with people is non-confrontational. It’s supportive and community-based.”

Anker and Ainuu begin ascending a boulder field, and the unceasing hum of highway traffic stays with us, even as we move away from it. Above the boulder field, the trail turns to dirt, and we zigzag short, tight switchbacks Anker calls Nepali switchbacks—and he would know. In addition to a generous handful of alpine expeditions in the Himalaya, in 2003 Anker and his wife founded the Khumbu Climbing Center in a remote area on the way up to Everest Basecamp. The climbing center provides skills and knowledge to Nepali climbers and high-altitude laborers to arm them with more tools to stay safe doing some of the world’s most dangerous work.

The switchbacks are steep but well-trodden. In addition to setting the routes on the rock, developing a climbing area includes infrastructure—building accessible trails and clearing out belay areas. While Anker and his crew haven’t shared the area yet with the public, it’s on forest service land. Different areas have different rules about developing climbing areas and bolting rock, and he considers himself lucky to be able to do so in the Gallatin Canyon, an opportunity he credits to years of building good relationships and open communication with forest service rangers. That, and “having a lot of brownie points in the climbing community,” Ainuu adds.

Anker turns the corner at the top of a saddle and leads the group into a small canyon that glows an ethereal green in post-storm humidity and softened sunlight. The traffic hum is replaced by the rush of a creek cascading over a mossy cliff. Anker and Ainuu set up below the waterfall, stepping into their harnesses, counting draws and roping up.

“Not everyone is gonna go out rock climbing and do things like that, [but] we need to work together towards that common goal, which is decency, solving things for the future and investing in the future.” – Conrad Anker

Anker climbs first. He takes a deep breath, wipes the bottoms of his shoes on the insides of his calves and pulls himself up on the first of many bulging holds. The waterfall makes it hard to hear much, but they don’t need words. Anker clips into the first bolt and looks down at Ainuu over his left shoulder and nods. Ainuu nods back and extends Anker some slack. Anker pulls the rope up and clips it into the draw.

Community in any form acts as a sort of lexicon for a particular language, Anker asserts. In climbing, this language is belay. This language is trust.

Climbing is often a dance between grit and grace, but on this route, Anker ascends fluidly. It’s cliché, but I think to myself how watching Conrad Anker climb is like watching Beethoven play Für Elise or Michael Jordan shoot a jump shot. There’s something different about the greats. Their talent is an expression of a nearness between them and the thing. Anker doesn’t just climb. He’s in relationship with climbing.

He completes the route, the rope attached to the wall in a lightning-bolt pattern. Ainuu lowers him, and when Anker reaches the ground, he folds his hands in prayer and bows to his climbing partner.

This language is gratitude.

It’s Ainuu’s turn. Before he starts, Anker offers beta. “All the holds are positive,” he says. “You just gotta get scrunchie to ‘em.”

This language is teaching.

Ainuu climbs. With his toes on a thin ledge, he clips the fifth bolt, reaches to a knob of rock above and hoists himself up, his hips tight to the wall. “Yeah, Manoah!” Anker calls, stretching out the end of Ainuu’s name like a sportscaster might. Ainuu reaches the top and threads the rope through. “Awoooooo!” Anker howls like a wolf.

This language is celebration.

Anker lowers Ainuu, and his face is soft, content, proud of the boy who calls him uncle.

This language is love.

Climbing courted Anker when he was young. He was exposed to the outdoors early, enjoying annual pack trips with his family into the Sierra Nevada, but his connection to rock and ice formed in his teen years. “At age 14, I had this epiphany and that was it, everything I’m gonna do is to go climbing and spend time outdoors,” he says.

Fast forward to 1987, when Anker along with climbing partners Robert Ingle, James Garrett and Seth Shaw took off in a ’72 Ford Econoline on an expedition to the Kichatna Spires in Alaska. The trip was funded by a $400 American Alpine Club grant for young climbers. That was back in the day, he says, before the sponsorships and films and bona fide career.

“It was when you were happy to get a raincoat and a sleeping bag and a tent,” he laughs. “You’re still living on top ramen, living the dream.”

Things aren’t the same—not only for Anker, but for climbing in general. “It was vastly different 30 years ago,” he says. “Free Solo hadn’t changed the world of what climbing was, and these landmark achievements—Lynn Hill freeing The Nose [on El Capitan]—still hadn’t happened that brought climbing into the public awareness.”

Indeed, Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi’s film documenting climber Alex Honnold’s free solo of the face of Yosemite’s El Capitan hoisted climbing out of the depths of dirtbag relegation and into the spotlight when it won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2018; and in 2020, sport climbing debuted in the Olympics. Unlike when Anker found it, today climbing is in the mainstream.

“Now it’s like, ‘Oh, I saw a Red Bull advertisement on YouTube, I’m going to the climbing gym, and then you climb 5.10 your first day out because it’s a bucket haul,” Anker says. “But back in the day it was like backpacking, and brown 1-inch webbing on all the carabiners, and this community of like, I’m going to teach you how to belay because you literally have to have someone show you the ropes.”

As with any populous facing rapid growth, the climbing community faces a choice: subscribe to the gatekeeping ethos that often tinges outdoor recreation, or hold the door open. Anker’s opting for the latter, and he’s got the sway to pull the community with him. It’s a stance he’s taking in his own town.

Twenty minutes from his house near downtown Bozeman is Hyalite Canyon. Hyalite is the most heavily visited recreation site in Montana and somewhat of a climbing mecca, especially during the winter when climbers from near and far flock to the nearly 150 ice and mixed routes in a mere 3-square-mile area. Here, Anker reigns supreme.

Every climbing area has a steward, or a sort of steward, Anker says. Hyalite is just one of many places Anker fills this role. He knows that label comes with a responsibility to determine the tone of a place—to set the bar for community.

“On the trade routes in town, let’s make them safe, let’s make them accessible, make them welcoming,” he says. Hyalite sees 40,000 visitors a winter, he says. By welcoming new people, we’re not destroying any construct of ‘wilderness.’”

Anker met Ainuu at Spire, Bozeman’s local climbing gym, something like seven years ago, after which Anker joined Ainuu and his friends in Hyalite to climb at an area called Practice Rock. After that, Ainuu says Anker played a role in getting him into ice climbing. That first season, Ainuu says he went to Hyalite 40 or 50 times and was hooked. Today, he joins Anker as a North Face-sponsored athlete. Last year, the now-28-year-old climbed Mount Everest with a team called Full Circle, the first all-Black team to summit Everest. The seven-person cohort, plus eight Nepali guides, nearly doubled the previous total of 10 Black people to summit the world’s highest peak.

Ainuu moved from Washington to Montana in 2013 to study geology at Montana State University. Born in Harbor City, California, Ainuu spent the first few years of his life in Los Angeles. When he was 9, his parents moved him and his sister to Spokane, where he was introduced to skiing and some climbing, but it wasn’t really until he moved to Bozeman that he became invested in climbing.

Anker is nearly 30 years Ainuu’s senior, but it doesn’t really make a difference when they’re climbing. After years now of sharing a rope, Ainuu considers Anker a mentor.

“[Conrad] is one of the most … famous climbers, but he’s always taking new people out climbing, and pushing not just the sport, but our community, and also politics. He’s using his platform to make a change,” Ainuu says. “… I share a lot of the same views, and climbing is a cool way to experience empathy, I think, because the thing is, we could be so different, but if we climb together, we’re doing the same thing. And it’s all good.”

Community is not stagnant in time, Anker suggests, but rather generationally expansive. People are vessels of wisdom, and community is the container in which it’s shared.

“In any community, there’s a collective of people, from those with wisdom and experience to those that are young and that are getting into it,” Anker says. “And so all of them serve a point in time and so when I was mentored, starting with my dad’s buddies and my dad, and then I had a mentor that was 14 years older than me, they helped me out. Now I’m mentoring other people and I’ve been doing that for as many people as I can.”

One mentor Anker has discussed in myriad interviews is Terry “Mugs” Stump, an acclaimed climber whom Anker credits as his inspiration for climbing Mount Meru, an ascent that not only was captured in an award-winning documentary, but one that Anker has described as the culmination of all he had accomplished as an alpinist. Stump died when he fell into a crevasse while descending the South Buttress of Denali in 1992.

As much as partnership is a pillar upholding the climbing community, loss is its counterbalancing contra. Again, Anker compels the religion of gravity in which death is doctrine. Loss is a part of the climbing community; in fact, he says it’s what makes it significant.

“That is why climbing is so special … it’s because we die. And that cost makes it so real,” he says. When he talks about this, Anker closes his eyes, and it’s as if he leaves the room. He takes deep breaths until he’s ready to return. There’s a shift in philosophy when you discuss death at such a scale.

“We have this one life to live,” he says. “There is no afterlife. We’re ruled by the laws of the universe here, by gravity. We struggle with gravity as a way to worship gravity and eventually gravity is going to win and … our carbon is going to be recycled back into this earth. And when that happens, great, and you lived in the moment, but at this point, [at this] age, I’m far more accepting of it.”

He accepts it, and he also has his own ways of honoring it. Anker’s named a number of routes in Montana, as well as all over the world, for people he’s lost. Here at the Retirement Wall, he and Ainuu developed a route they call Yeti Cowboy, named after late local climber Travis Swanson, who in 2019 died in a climbing accident on Mount Cowen in the Absaroka Range. When Anker climbs these routes, it transforms the community’s paradigm of loss to one of celebration. Each move on the rock is like a dedicated line of poetry, the route itself an elegy. We don’t remember these climbers for how they died; we remember them for what they loved.

Above the waterfall sanctuary, a vast wall invites Ainuu and Anker for their last climb of the day. These routes are long, many with more than one pitch of continues jugs and ledges. Anker rests on a rock and gobbles a granola bar. So much of a day out climbing looks like this: the moments in between pulling on rock spent talking, eating, laughing, remembering. To an outsider, climbing can appear a solitary act. But it’s far from that.

Anker, who even late in life is pulled in so many directions, seems ever present in each moment he inhabits. Tomorrow, he’ll sit in front of a camera for another interview before celebrating Mother’s Day with his wife and sons. Then he’ll board a plane to Alaska for more filming, in between Zoom calls for a nonfiction writing project which he’s giddy about (the project, not the Zoom calls). He jokes about his endless list of to-dos, but there’s no question that he’s here with us, in the Gallatin Canyon, completely. It’s what he loves about climbing.

“There’s something about climbing because it activates the very oldest part of our brainstem and uses the front part of it— you know, this is autonomic function,” he says. “But then we use the prefrontal which is cameras and cars and TikTok and Republican obstructionists and all the other crap that we have to deal with. But when you go climbing all of a sudden that’s out of there. You have to be in the moment.”

Anker’s spent much time in this ever-present space, clinging to the side of mountains most of us will only ever see in his films. But even this sport, that demands alertness and complete focus in the moment, has something to teach us about foresight.

“Our generation, where we are now, we need to think about not doing harm to future generations … and I think climbing is that way because it’s a long-term goal that you don’t always get, and that teaches you to appreciate the now but also to prepare for the future,” Anker says.

Anker speaks about climbing as a sort of holy book for community, but his recent work on the athlete alliance for environmental nonprofit Protect Our Winters (POW) and related advocacy work has him translating its lessons beyond the crag.

“Not everyone is gonna go out rock climbing and do things like that, [but] we need to work together towards that common goal, which is decency, solving things for the future and investing in the future …” he says.

Anker is a leading member of POW’s athlete alliance, with notable stories about mobilizing entire live audiences to engage in political calls to action as proof.

“Conrad is an inspirational spokesperson on the importance of climate advocacy and civic engagement,” said POW Executive Director Mario Molina. “He is a draw for outdoor community members to POW events; he has access and influence with elected officials and decision-makers at the local, state and federal levels. He is bold in his positions when he knows them to be right, which is catalytic in moving our community towards action.”

Equally as illustrative of Anker’s community work is his resume with The North Face, one of the outdoor industry’s leading brands. Anker started working for the company 40 years ago as an employee and 36 years ago as a sponsored athlete, 26 of those years serving as the brand’s athlete team captain. After what he describes as a self-reckoning with his privilege as a white male, he’s involved himself in Diversity, Equity and Inclusion work with The North Face. Some of this is done through Memphis Rox, a nonprofit climbing gym in Memphis of which Anker is on the board whose mission is to “bring rehabilitation, healing and a renewed sense of hope to challenged communities by providing a climbing facility and programs that foster relationships across cultural, racial, ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds,” according to the organization.

In 2020, Black Ice, a film Anker said he came up with, screened across the country and showed the story of a group of aspiring ice climbers from Memphis Rox journeying to Montana where they were mentored by Anker, Ainuu and Fred Campbell. Anker says he’s connected The North Face with these projects as a sponsor.

Anker is in his age of advocacy, fighting for community that extends beyond rock walls and frozen waterfalls. He calls it “good trouble,” a nod to U.S. Congressman and civil rights activist John Lewis, of whom he has a 3-foot-by-5-foot portrait of hanging in his office.

Good trouble seems appropriate. He gets lit up when he talks about the societal infractions that ail him: violent capitalism, a lack of accountability for those in power and a penchant for immediate gratification. During our interview at his home, he becomes riled, turning his gaze directly into the camera as he condemns recent action in the Montana Legislature that saw transgender Rep. Zooey Zephyr banned from the House Chamber for breaking decorum when speaking against bills she argued would harm trans people and their community.

“Damn you elected officials in Montana that are driving on the wrong side of the road and you know who you are,” he says. “You know what the f*** you’re doing. Stop playing chicken with national debt; taking the belay out while we’re climbing, tying knots in each other’s rope.”

His anger is earnest, primal even, and in these spells of passion, he embodies the spirit of saboteurs for justice the likes Edward Abbey’s fictional George Hayduke from The Monkey Wrench Gang. One of the book’s quotes hangs over his head like a halo: “There comes a time in a man’s life when he has to pull up stakes. Has to light out. Has to stop straddling, and start cutting, fence.”

Passionate as he is, Anker isn’t cutting any fences these days. He’s leading campaigns to get people to the polls; he’s writing op-eds; he’s lobbying in Washington D.C. It’s his medium of change, his outlet for unrest. But the fight lives in him like a fire; he demands more.

The week before we met, Anker was toiling over an op-ed he was writing for Bomb Snow magazine. The topic: climate optimism. He scoffs a bit when he says these words together, like they’re sticky from being glued together. Maybe he doesn’t think of himself as a fountain of faith, but seeing him out on the rock, speaking belay, his movement congruent with land, with self, with partner, I bask in that ethereal green light and the mist of the waterfall and feel its promise.

This language is hope.

Bella Butler is the Managing Editor of Mountain Outlaw magazine.